Dealing with a Difficult Colonoscopy

ENDOSCOPY

5/7/20247 min read

Passing a colonoscope through a 6-foot-long colon is a challenging task, not least because there is an infinite variability in the anatomy of the large bowel. Anatomic heterogeneity is matched by the wide variation in skill level within the fraternity of colonoscopists, and the combination of colon and colonoscopist is manifest and summated in the degree of difficulty of any examination. Attempts at measuring difficulty are obviously subjective and depend not only on colonic tortuosity and colonoscopist skill, but also the degree of anesthesia provided to the patient. It is easier to maintain patient comfort while intubating a tortuous colon when the patient is completely asleep, and much harder when the patients is lightly sedated with versed. However, some of the techniques mentioned here are harder to apply when the patient is asleep…such as change in patient position.

The data presented here do not include anesthetized patients, nor do they include patients given narcotics. The other important factor impacting difficulty is the presence of stool. The most difficult colons are those that are tortuous, with residual liquid and solid stool, in an awake patient.

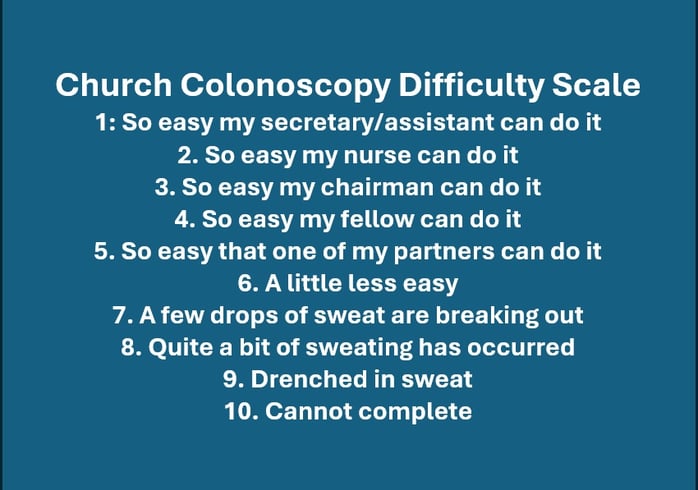

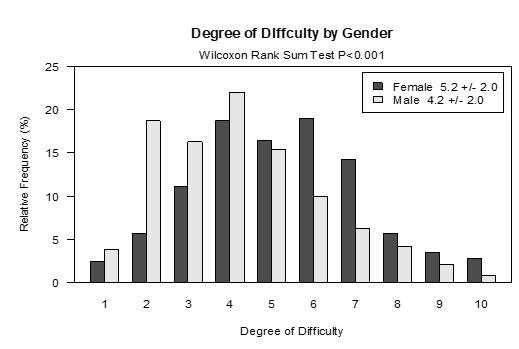

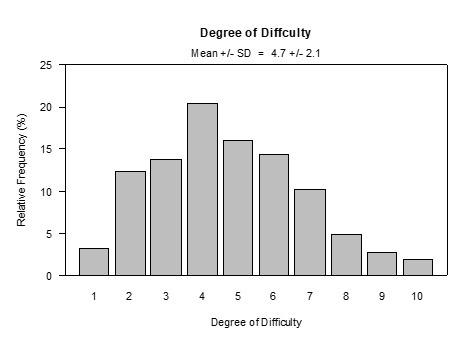

I have come up with my own difficulty scale for colonoscopy, and I have tried to describe the categories in a way that is understandable to every colonoscopist. I have applied this scale to a series of consecutive outpatient examinations done in awake patients to show the distribution of difficulty in this series. It shows the expected bell-shaped curve. The mean difficulty level of 4.7 validates the scale, remembering that a 10 means an incomplete examination. Plotting degree of difficulty for biological men and women shows what we all know, that women have a longer, more tortuous colon than men.

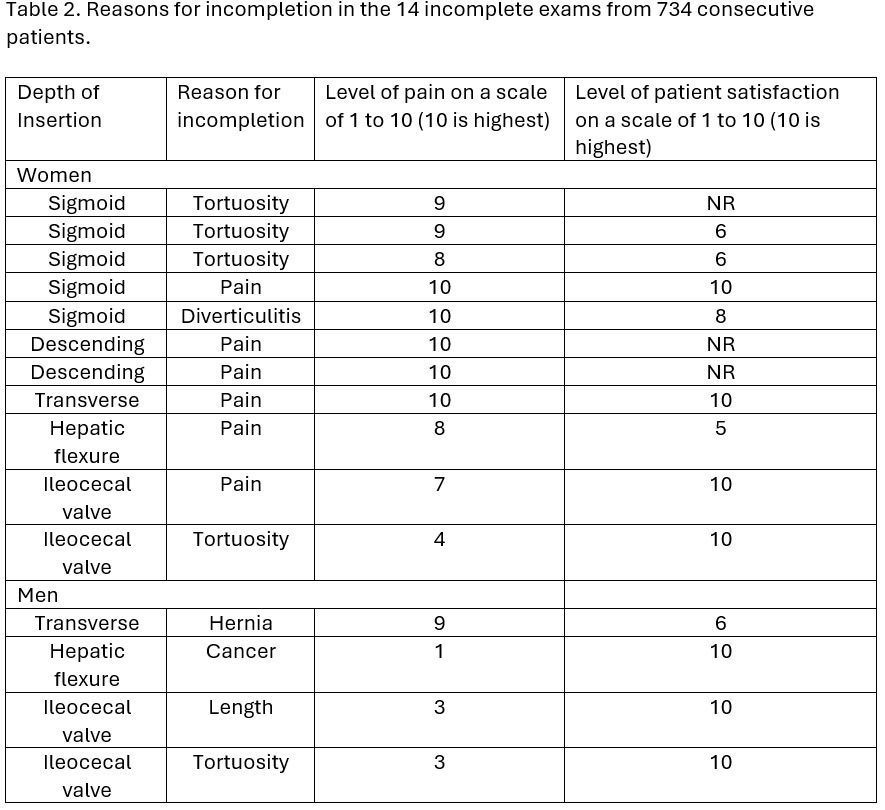

Table 1. Church Difficulty Scale

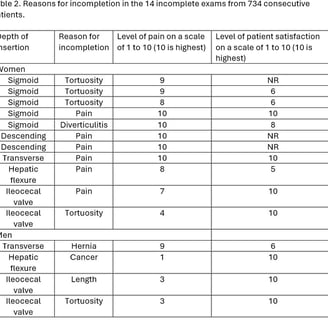

The following data are from a consecutive series of office colonoscopies done by yours truly for 734 patients over 16 months. 47% were women. The overall completion rate was 98.1%, with incomplete exams in 11/346 women and 4/388 men. Overall degree of difficulty is plotted in Figure 1, with the same data given for men and women in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Histogram of degree of difficult for the entire sample.

Figure 2. Overlapping histograms of degree of difficulty by gender

Here are the commonest causes of difficulty for a colonoscopist:

Pain: pain during scope insertion is usually due to stretching the mesentery of the colon, and this happens when there is a loop. The key to minimizing pain is to minimize looping. Sometimes you must push around the apex of a loop before you can shorten it, and this is painful for the patient. Loops that are fixed by adhesions cannot be shortened and cause constant pain. (see #4) Of course, general anesthesia takes the pain away which doesn’t help you to learn shortening techniques: but it’s good for the patient at least.

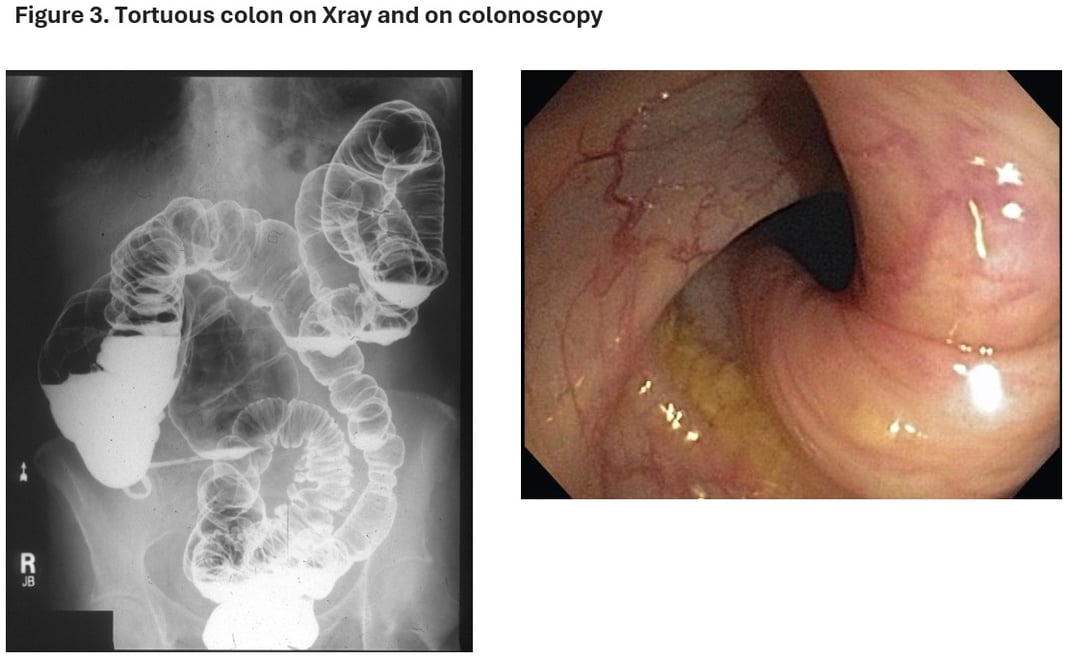

Tortuosity: The colon is tortuous because 6 feet of bowel are crammed into to space of an abdominal cavity, that is already quite full if small intestine and organs. The smaller the cavity and the longer the colon the greater the tortuosity. If someone has ordered a barium enema on the patient, often for constipation, don’t look at it as a road map for colonoscopy. It may put you off even trying the exam. (e.g., Figure 3)

Unzygosed colon: Most colons are retroperitoneal in their ascending and descending parts. The cecum, transverse and sigmoid colons have mesenteries and are prone to tortuosity but at least in the ascending and descending colon the bowel is fixed and straight, allowing loops to be removed and progress to be made. In some patients however (generally very slim patients, women, and joggers) the ascending and descending colons do not have a zygosis; they are unzygosed and on their own mesentery. This makes them easy to resect but hard to intubate, especially at the flexures. With these patients try to push through the loops and straighten the scope on the other side.

Pelvic adhesions: Pelvic adhesions can make the colonoscopist’s day miserable by attaching to the sigmoid and creating irreducible loops. The effect of sigmoid adhesions is shown well by our study comparing colonoscopy in women who have had a hysterectomy and those who have not. Patients who had a history of hysterectomy had significantly lower colonoscopy completion rates (89.2%) and significantly longer mean examination time (28.9 +/- 12.3 minutes) than those who had not, and more of them required sedation with benzodiazepines (88.7%) than the other groups.

Diverticular Disease: Diverticulosis also affects the sigmoid colon in a percentage of patients that increases with age. In a minority of cases the changes produced by chronic diverticulosis: colonic rigidity, tortuosity, narrowing, and the presence of multiple large diverticula, make insertion of a colonoscope tricky. Under these circumstances it may help to scope “under water”. Fill the colon with warm water that will relax spasm and allow recognition of the lumen.

Spasm: Colonic spasm is most intense in the sigmoid colon, although occasional waves of spasm happen in the right colon too. Attempts at intubation should stop when there is spasm. Wait for the bowel muscle to relax, which it always does. Blowing more gas to overcome the spasm is a bad idea as you will only blow up the proximal colon. Use body temperature tap water to relax the spasm…its cheap and effective. Giving antispasmodics is unnecessary, expensive and has side effects. In the right colon the wave of spasm will drive the scope out but don’t fight it: retreat before the wave of contraction but keep the scope as stable as you can and when the spasm stops the bowel will open up and you will easily regain your position.

Obesity: obese patients have a lot of mesenteric fat that smooths curves but prevents shortening of the scope. If you cannot shorten an obese loop, you can push through it without much pain for the patient. The trouble is that the loops, and the long transverse colon, eat up the scope. You may reach the hepatic flexure with the scope inserted to the hilt. Try moving the patient from side to side, or side to back, or back to side. Use pressure.

Short mesentery: Remember that colonoscopy causes pain by stretching the mesentery; when the mesentery is short, it is easily stretched, and pain comes early and is more severe. This is much more common in younger men, who don’t have the tissue softening effect of estrogens. They may need increased analgesia or deeper anesthetic, and some just cannot be scoped.

The inaccessible cecum: You have made it around the hepatic flexure and see the cecum in the distance. You can taste the tea or coffee waiting in the tearoom. But the scope will not enter the cecum no matter what you do. Pushing causes a proximal loop, and pain for the patient. You are tempted to give up, to be happy looking down into the cecum without actually getting down into the cecum. This is how cancers are missed. The trick is to turn the patient on their right side, and 80% of the time you will find the scope slides into the cecum with no difficulty. This is because in these patients the cecum is not aligned with the direction of the ascending colon but takes a sharp turn to the side.

The dirty cecum: sometimes you reach the cecum (well done!!!) only to find it is coated with slimy and sticky bile. You try and wash it out but it takes forever. Sometime the sticky sliminess coats the ascending colon. This is a problem because the right colon is home to sessile serrated lesions, precursors of CIMP-high cancers. They are low profile, sessile polyps identified by their mucus coat and easily obscured by bile. The bile is there because there has been too long between the prep and the exam. The patient cleaned out well, but the colon has started the reloading process. The solution is to time the prep so that there is a minimum time between the end of the prep and the exam. A patient with a morning exam can have all their prep the evening before, but appointments after 10.30 may see some bile appearing in the cecum. A patient with a late morning exam or an early afternoon exam should split their prep, and a patient with a mid to late afternoon exam should take all their prep the morning of the exam. I solved the problem by prescribing 4mg Imodium to be taken when the prep-induced diarrhea ends, but that was just me.

You can optimize the experience of colonoscopy for everyone by adopting the following principle: ”SHORTEN THE COLON”. This means collapsing the colon over the scope so that a 6-foot-long colon is examined by a 2.5 foot long scope. This makes the examination more comfortable, withdrawal more accurate and polypectomy safer. “How do I shorten the colon?” you ask. This is how:

KEEP GAS INSUFFLATION TO A MINIMUM

TAKE THE “INSIDE LINE” (like driving a race car around a track)

DEFLECT ”UP” WHEREVER POSSIBLE (torque the scope around so that you can deflect up…it’s that important)

TORQUE AROUND CURVES

WITHDRAW AROUND CURVES (with torque)

“BOUNCE” AROUND CURVES

SUCK AROUND CURVES

SHORTEN SCOPE AND WITHDRAW LOOPS AT EVERY OPPORTUNITY

SPLINT LOOPS

CHANGE PATIENT POSITION

ASK PATIENT TO HOLD BREATH

REFERENCES

Hull T, Church JM. Colonoscopy--how difficult, how painful? Surg Endosc. 1994; 8: 784-7.

Garrett KA, Church J. History of hysterectomy: a significant problem for colonoscopists that is not present in patients who have had sigmoid colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010; 53: 1055-60.

Church J. The unzygosed colon as a factor predisposing to difficult colonoscopy in slim women. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002; 55: 965-6.

Dean M, Valentino J, Ritter K, Church J. A novel endoscopic grading system for prediction of disease-related outcomes in patients with diverticulosis. Am J Surg. 2018; 216: 926-931.

Church JM. Warm water irrigation for dealing with spasm during colonoscopy: simple, inexpensive, and effective. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002; 56: 672-4.

Causes of Difficulty:

If we want to be able to deal with challenging colons it is important to recognize the causes of the difficulty of intubation. A review of the reasons for incompletion from the series presented here highlights the most common causes of difficulty. These are shown in Table 2.